Balloon Wars: A War Contractor’s Memoirby Rob Crimmins

Balloon Wars: An ISR Operator's Account of the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

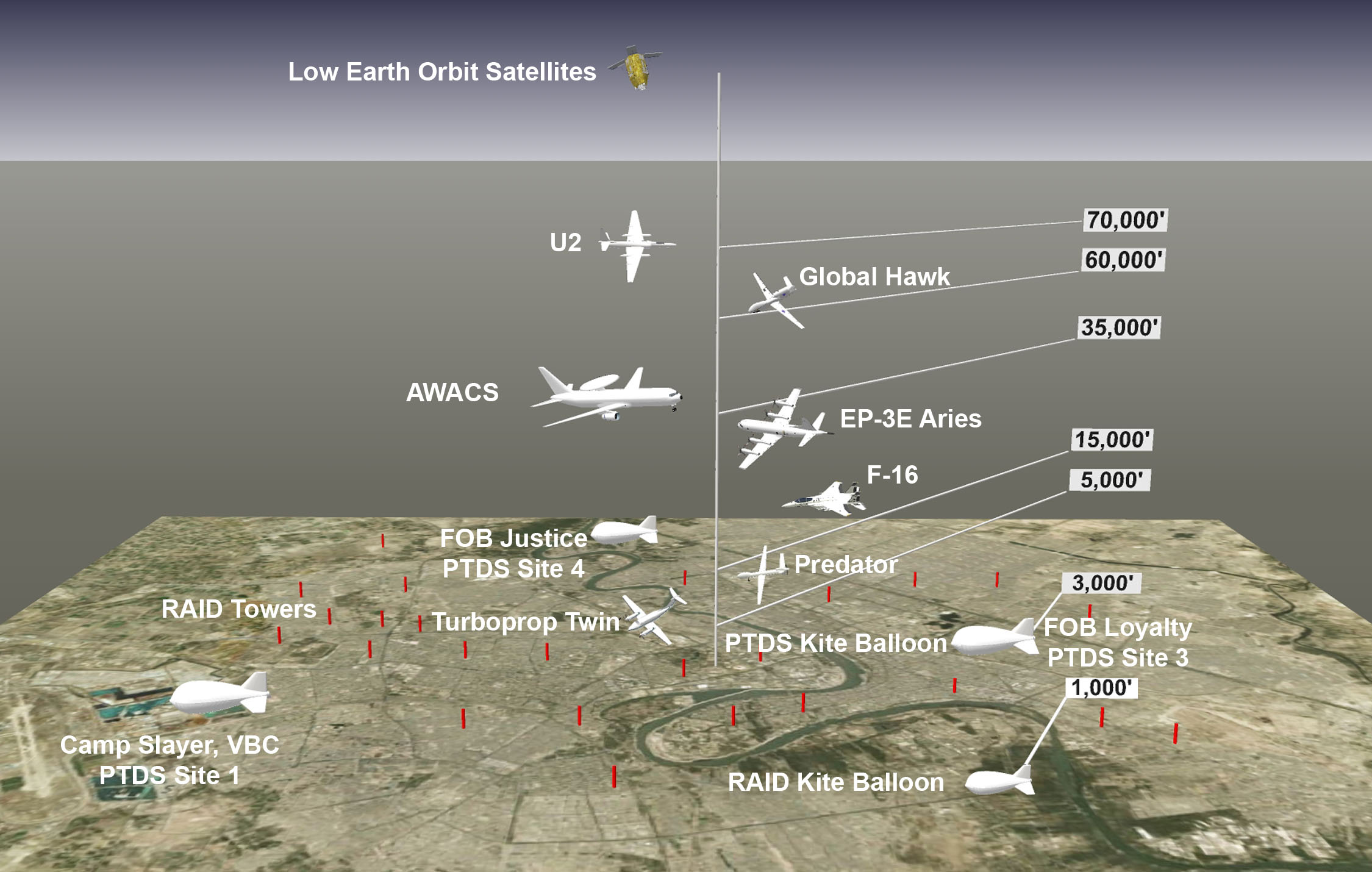

In 2007 I went to Baghdad as a civilian contractor with Lockheed Martin, the big defense and aerospace company. My son, Dan was in the Army at the time on his second deployment in Iraq with the 3rd Infantry Division. He’d been there in 2005 in Ad Dawr, near Tikrit. His pictures and accounts and the movies I’d seen were among the sources for my expectations because I had no military experience.The program I was on was the Persistent Threat Detection System or PTDS. “PeeTids”, as we called it, is a kite balloon, also referred to as a "tethered aerostat", that carries a weapons detection system and a very sophisticated camera. It's an “ISR” asset. ISR stands for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and the PTDS system is an element of the ISR Network which also includes satellites, manned aircraft, drones, other balloons, tower cameras and weapons detection systems. Special Operations, the CIA and people or units that are considered Military Intelligence aren’t part of the ISR Network but those operators and units depend on the ISR assets and network to find and kill the enemy. Conventional units use ISR assets for base defense and mission support too. The ISR network gives the United States the high ground and the PTDS system gave me a birds-eye view of the Iraq War and “The Surge”.

synopsis

1. Worst Month of the War Was Our First There2. Battle in Al Atiba'a

3. Forward Operating Base Loyalty

4. The Pack Smelled Blood

5. Fire Base Waza Khwa, Paktika Province

6. The Karez: A Symbol of Afghan Character

7. Captain Ellis

8. The Good & The Bad - From Zormat To Iberia Iberia

9. Wrap It Up

SELECTED CHAPTERS

Chapters 1 & 2 - PTDS & the ISR NetworkChapter 12 - Battle in Al Atiba'a

Chapter 17 - Muqtada al-Sadr

Chapter 33 - Urged to Jump

Chapter 40 - Mortar Attack

Chapter 78 - UTAMS Repair

Chapter 79 - IRAM - A Deadly New Weapon

Chapter 82 - Bagram and Waza Khwa

Chapter 86 - Captain Ellis

Chapter 87 - 9th Inflation and The Karez

Chapter 91 - Ickbar and the Bachi Bazi

Chapter 116 - Just Living

Click here to comment on any of the Balloon Wars sample chapters

We both assumed I would be safer than Dan but I did end up being in far more hostile neighborhoods than I expected, exposing myself in ways that soldiers rarely if ever did, and being repeatedly fired on. And there were times, because of Skype, when Judi actually witnessed the attacks. Once, I was outside while she and I were conducting a chat when we both heard the woosh of the Katyusha rocket. She watched as I fell to the ground for cover, and heard the explosion that followed the impact.

In June of 2008 I went to Afghanistan and Danny was out of the Army so things got better for Judi.

Worst Month of the War Was Our First There

May & June, 2007 – Camp Slayer, PTDS Site 1

Period in Balloon Wars Part 1 (chapters 1 through 23)

2007, the year of The Surge, was the worst year of the Iraq War for the United States. May was the worst month of that year with 126 U.S. military deaths and thousands of Iraqis had been dying due to the war each month for the previous two years. We landed in Baghdad on the afternoon of Saturday, May 5th.

I was fifty-one years old, which was about the average age of the nine guys on our team. We were all employees of Lockheed Martin and most of us had been hired two or three months before. I was the only member of our team who wasn’t ex-military, or military contractor with extensive, recent experience in one or more war zones.

We were “Team 4”, the third PTDS team to operate in Iraq. The first group had been in place since 2004 on Camp Slayer in Baghdad. One of the members of our group was with the original team but he had been off the program since shortly after the first site was set up in 2004. Team 2 had recently started operations in Afghanistan and Team 3 had been at FOB Loyalty in East Baghdad for the previous three months, since February.

By 2014 there were dozens of sites in Afghanistan. Site Four was eventually installed on FOB Justice in north Baghdad. That was where my team and I were supposed to end up but it didn’t work out that way.

The kite balloon, or “tethered aerostat”, that we were sent to Baghdad to assemble and operate would float a L3 Communications, Incorporated, “Wescam” MX20 gyroscopically stabilized, multi-spectral, airborne imaging system, which is a very sophisticated and expensive camera. It’s the same as the one carried by the Predator drone and It’s actually three cameras, two “electro-optic” cameras, one wide angle and the other with a narrow field of view for zooming in on things and the third camera was infra-red for night vision and seeing through haze.

The balloon also carried the base station for a weapons detection system called UTAMS. The Unattended Transient Acoustic MASINT System listens for certain acoustic signatures, such as weapons fire, so the system can react, and the camera can be automatically pointed to, the source of the sound. It didn’t always work but when it did the change was abrupt. You could go from a routine scan of a road you’d been watching every morning for the last three weeks and seeing nothing but stray dogs to an IED explosion or troops under fire in a second. (There’s an acronym within the UTAMS acronym. MASINT stands for Measurement And System Intelligence.)

The balloon that the camera turret and the UTAMS base station were laced to is similar to other lighter-than-air-craft like blimps. Both are made of the same materials and in a similar fashion. Corporate and military people don’t call them kite balloons though. That’s not sexy. To them they’re “aerostats”, which is right but it’s less descriptive because an aerostat is any lighter-than-air-craft that can remain at a fixed altitude. A toy balloon on a string is an aerostat.

I first saw kite balloons in World War II newsreels. They were used then to prevent low level strafing and bombing runs and they were called “Barrage Balloons”, but, in the language of “aerostation”, the field of air vehicles and conveyances known as “lighter than air”, a field related to but distinct from “aviation”, an aerodynamically shaped balloon on a tether is a kite balloon. That’s their proper name.

The roots of aerostation go back to the eighteenth century with the hot air and hydrogen balloons in France that Benjamin Franklin admired, to Count Von Zeppelin in Germany and the first aerial bombardments in World War One, to the Hindenburg and US Navy dirigibles in the 1930s and Navy blimps used for anti submarine warfare in World War Two and The Cold War.

Modern airships include complicated hybrids, one of which I helped build, and huge, oddly configured non-rigid airships mostly for military missions but also for heavy lift and transportation. The “tethered aerostat” programs, to use the nomenclature of the companies that developed them, has a lot of history too, going back to the late 1960s. I was part of that too. I worked on the TARS program, which is the Tethered Aerostat Radar System, in the 1980s, and SBAS, the Sea Based Aerostat System. I was that program’s first Project Engineer. The Sea Based Aerostat System is the one on which PTDS is based. Both are mobile systems, with balloons of roughly the same size. The PTDS system requires disassembly and roads to get about but it’s a mobile system too. The one that went to Iraq with us was assembled in Florida first and we put it back together again in Bagdad and then it was moved to another location in the city a few years later. Taking it apart and putting it back together wasn’t something that you’d want to do very often but you could when you had to.

We put ours together during the second week in May of 2007 on Camp Slayer on the Victory Base Complex. The VBC was the primary location for American forces in Iraq. It included Multi National Division Baghdad Headquarters, where Generals Petreus and Odierno lived, the international airport, numerous Army camps and multiple palaces and residences formerly occupied by Saddam Hussein and his notorious sons Uday and Qusay.

When we landed on that Saturday morning after thirty-seven hours in airplanes, airports and other travel terminals and conveyances we were met by the technician who maintained the UTAMS equipment, not one of the PTDS team members. I didn’t notice at the time but it was the first of many, nearly continuous slights and indignities that the Lockheed crew-members would be subjected to by the men who were already there. The details hadn’t been explained to me but Lockheed had won the O&M (Operations and Maintenance) contract and the men who had been at Site One for the previous three years, employees of Telford Aviation, would have to leave or apply for the job with Lockheed and take a pay cut. None of them liked it and my team and I would be repeatedly reminded of that over the next few months.

The tech who came to pick us up, was a pretty nice guy, and he had a plan. After leaving Iraq he was going to get elected mayor of his small town in Louisiana then win a Congressional seat. He had a bad lisp and was hyperactive so those idiosyncrasies would have to be overcome, but it could happen. It seems he’d read the “Iraq Transitional Handbook”, a well written and very useful DOD publication, because he acted as he should have with the Iraqi storekeeper, from whom I’d bought the SIM chip for my phone. After shaking the Iraqi’s hand, with a mild grip, he placed his right hand on his left breast and said, “Assalamu ‘alaykum”, “peace be with you”, the standard Arab greeting. Mike then asked about the man’s family, another important custom. The young, dark eyed fellow, glad for the rare show of manners, indulged Mike even though he was aware that it was a display. I could see that Mike would behave as required on the campaign trail or on Capitol Hill.

It only took us a few days to get ready to inflate the balloon but because of the weather and another problem with assigning radio frequencies we didn’t inflate the balloon until the following Sunday, May 13.

For the next few weeks after the balloon was inflated we were “on mission” most of the time, coming down only to avoid bad weather or to add helium. There were a lot of IEDs, Vehicle Born IEDs and suicide bombers in Baghdad in 2007. Nationwide there had been over 20,000 road side bomb attacks in the first seven months of the year. A lot of indirect fire (mortars and rockets) was being launched too so there was a tremendous need for reconnaissance.

The west end of the infamous Rt. Irish was right under our nose. It entered the airport property less than a mile from the balloon site. In May of 2007 “Irish” was not “the most dangerous road in the world” as it had been dubbed in 2005 when the charge for one car for the ten kilometer trip from the airport to the Green Zone was $3,000. In fact that portion of the city, the southwest quarter, was relatively quiet compared to the east side, which included Sadr City. FOB Loyalty, which housed Balloon Site Three was over there and it was a favorite target for many of the Mahdi Army cells operating out of Sadr City and elsewhere.

The Green Zone, in the middle of town was getting a lot of fire then. One night the operator at Site Three spotted a rocket team in a soccer stadium firing on the compound that housed the American Embassy. That was an incident that PMRUS (Program Management Robotics and Unmanned Systems), the Army office we worked for, qualified as a “good news story” and about the only one that made the news back home. The rocket team was killed with missiles and the video from the PTDS camera was declassified and shown on the CBS Evening News.

It wasn’t as intense as it was elsewhere but there was warfare around Site One.

Battle in Al Atiba’a

Balloon Wars chapter 12

One of my first times on the camera we saw a running battle in Al Atiba’a, one of the neighborhoods just outside the wall. At about 2000, which was about an hour after sunset, I had just come into the GCS to take my hour on the camera, relieving Don who moved over to the mIRC station just as the camera “slewed” to Al Atiba’a, the Sunni neighborhood a mile east of the site. “The mIRC” is the internet chat application that’s the primary means of communication between the PTDS operation and the supported TOC (Tactical Operations Center).

Most of the time the UTAMS “service request” doesn’t take the camera to the exact spot of the sound it’s acting on but this time it was close so it only took a few seconds to locate a one-story, Iraqi Police station that was under fire. Police were on the roof taking cover behind the parapets as three vehicles entered the courtyard and several IP jumped out of the trucks and took up positions around the building. The police on the roof were apparently unsure where the enemy was. I zoomed out far enough to see about six houses across the street to the north and quickly panned west and then back east to look for the shooters. When I found them the first thing was to count them and identify their weapons and have Don enter that in the mIRC chat. The barrel on one of the weapons was white so we knew it had just been fired. The hot shell casings on the ground indicated he’d been firing from this position already. In a second another guy came into the frame at the top and one of the others ran north with him so at that point fighters were in multiple locations.

To keep track of the changing battle with one camera I had to zoom out. In the wider shot I could see the guy firing on the IP station and the others who were on the move. The first bunch split again with half of them running to a house on the south edge of the neighborhood where they joined another group on the roof. The video feed goes to the TOC so the Army was watching and responding. At times they told me what to do with the camera. Actually they told Jason Grantham, one of the Telford operators, what to do and he told me. Jason and Winston had come into the Ground Control Station as soon as they knew what was happening and I was real glad they did. Things were happening much too quickly to be communicated through the mIRC and I was too busy with the camera to use the phone. Protocol didn’t permit us asking what the Army was doing but our assumption was they were dispatching a Quick Reaction Force to the scene. One of the fighters on the roof fired an the RPG in the direction of a Shi’a neighborhood to the south, maybe to a specific target, but maybe not. A lot of these guys just fire and let the result be a matter of God’s will. From there the first group went north a few blocks to an empty lot where spectators watched them fire mortars into the same neighborhood they’d just fired the RPG into.

All the weapons were then put in a car and driven to a home nearby where they were stashed in a trash pile in the back yard. This mission was an outstanding example of what the system was capable of. The scenes here were used for training and promotion which is why they were de-classified originally and this mission was an outstanding example of what the system was capable of. It was gratifying for me as the camera operator. With the location of the weapons cache recorded, it wasn’t long before the Army was on the scene to pick them up. The camera reticle (the cross hairs in the center) remained fixed on the yard where the weapons were stashed. Two Humvees and a Bradley fighting vehicle in the top of the frame and two more vehicles in the bottom are on their way to capture all the weapons that were just used. One of the other overhead assets, maybe a Predator UAV, was probably following the car and driver that delivered them. We never heard if they caught the guy who drove away or any other details, which was typical for the missions at Site One. No one followed up in most cases either from our end or the Army’s. We just got our assignments, completed the scans, responded to events and went to the next task.

Forward Operating Base Loyalty

July August Sept and October, 2007

Balloon Wars Part 2 (chapters 23 through 55)

Leave was granted every four months and since everyone on a team started at the same time everyone was eligible for their break at the same time too. To fill in for the guys at Site Three who were on leave or quitting some of us on Team Four went over there. I got there on July 3rd. I was supposed to be there as the night shift supervisor for three weeks but on July 4th they made me Site Lead and I ended up running the site for four months. Site Three was starkly different from Site One and every other place I’d ever been. It was on Forward Operating Base Loyalty in East Baghdad, specifically the Baladiyat neighborhood. Previously it was the headquarters for Saddam’s Secret Police, the Mukhabarat, and a prison, so it got special attention from our pilots and troops during the invasion. Iraqi commanders in corner offices were hit and the buildings their subordinates occupied were smart bombed during the early stages of the invasion, if not the first night, but many of the buildings were left intact, so the US Army could occupy them later.

From the unclassified communications I’d been a party too, and they were extensive, I knew before I got there that the relationship with the Army was very bad and the operation at Site Three was in trouble. The day that I was made Site Lead I received a call from the Lockheed Program Manager and the Operations Manager. He was exaggerating but the program manager said that if things didn’t improve at Site Three the program would be in danger. He meant the contract because the Persistent Threat Detection System would go on without Lockheed Martin Aerostat Systems if need be but he was worried and he said that things had to turn around.

My first night there we worked on solving the main problem, which was patching holes in the balloon and stopping the leaks. It’s a high tech device, this aerospace inflatable with cameras and weapons detection systems laced to it, but the basics of the aerostat, a fabric assembly made with adhesive and heat seals, are simple. Its coated fabric that contains helium and if there are holes in it, it doesn’t.

Finding the holes is an uncomplicated and labor intensive exercise. It’s done by putting mildly soapy water on the balloon with a pressure washer and looking for bubbles and then patching the holes with adhesive and fabric patches. Sometimes holes can be seen without the bubbles but often they can’t so the same method used to find pinholes in inner tubes is used with aerostats and blimps and it’s what we did every night we could for seven weeks.

It had to be done at night. It was far too dangerous to bring the balloon down during the day. Rocket and mortar attacks were common, there was a sniper and RPGs were occasionally being fired at the guard towers.

That first night, another crew member and I went up to do it. It’s done from an aerial lift, way above the wall with a bright, white light to spot the bubbles. We were not only visible from quite far away we were a moving and very prominent feature of the skyline and at times less than one-hundred feet from enemy territory. At that time, when the Mahdi Army was wreaking havoc and had sanctuary in Sadr City less than three miles from FOB Loyalty, it was an insanely dangerous position.

A few days later we did it again. A couple hours before daylight, with sweat pouring out from under my ballistic vest and helmet, just about the time when I stopped thinking about our circumstances, we heard gunfire. Tracers came over the wall near the guard tower and toward us.

The troops in the tower fired back and more rounds came in. Terror seized me and I had the urge to leap out of the basket just like those who jump from burning buildings. Two broken legs seemed better than a rifle bullet in just about any part of my body. But rather than jump my buddy and I got as small as we could as I swung the boom away from the balloon and took us down, at a sickening slow pace.

The rest of the crew ran behind T walls long before we got down. When we joined them we talked about what happened and admitted to each other the balloon probably had more holes. We did that seven times in six weeks and eventually stopped all the leaks. After that the Army guarded us with troops in the neighborhood outside the wall and twice they had Apache helicopters over us the whole time the balloon was down.

Persevering through that difficult and dangerous task of repairing the balloon was an accomplishment I’m very proud of. Before that was done it couldn’t remain aloft for more than six days and had to be recovered without notice twice. Afterward we set a program record by staying in the air for twenty-five days and we always knew, with plenty of notice, when the balloon would have to be recovered. There were no more emergencies requiring mission interruptions and scrambling troops.

There were other things the crew did while I was in charge that resulted in turning the operation around and without question, saving lives. When I arrived there was no video feed from the PTDS camera to the BDOC, which is Base Defense. We were being fired on almost daily and the unit that was there to defend us couldn’t see what we could. THE best tool for seeing those who were shooting at us was right over their heads but they weren’t using it so we ran a cable from the TOC and installed a signal amplifier. From then on the big screen in the BDOC displayed the PTDS camera image instead of ESPN. We shut down the sniper who had been preying on us by working with the BDOC in ways the previous crews hadn’t tried. Some of the crew devised ingenious ways to use the equipment that bore fruit and I served on the anti IED and IDF working groups. We found new ways to use base defense systems, solved numerous operational matters, organized the site and got all the critical spares behind cover. The base commander let me attend the Commander’s nightly brief in the TOC and I was free to observe their operations at any time.

We fortified the site, which had been repeatedly damaged by indirect fire. Shortly before I got several crew members were nearly killed in a rocket attack. A lot of the crew quit, asked for transfer or refused to do certain jobs or work during times of day when attacks usually occurred. I didn’t like it then but I don’t blame them.

Despite our accomplishments and completely rectifying the company’s relationship with the Army I was told not to return to FOB Loyalty when I got back from my first R&R on October 2nd. I had no idea it was coming. The stated reasons were because I was abrasive and tried to tell the Army what to do. No civilian contractor can tell the Army what to do in a war and trying would bring an immediate and harsh rebuke and being abrasive shouldn’t matter if you’re helping win a war. Under those circumstances you need to be able to take more than abrasion but my boss on the FOB, a Major with a Napoleon complex and a hater of civilian contractors, disposed of us on a whim. When I was appointed Site Lead I was the sixth one at a site that had only been in operation for four months. I lasted three months, much longer than any of the others, but when the Major called for my removal my boss, just said, “Yes Sir”. It was ironic that it happened at a place called “Loyalty”.

The Pack Smells Blood

November, 2007 to May, 2008 – Camp Slayer and FOB Justice/Site 4

Balloon Wars Part 3 (chapters 56 through 81)

The memoir about my time in Iraq and Afghanistan, “Balloon Wars”, includes descriptions of events, people, cultures, travels, occupations and technology and it’s about the effect that such a life has on anyone who lives it.

The pitch for the movie might be, “Catch 22 or M*A*S*H at ‘The Office’, in Iraq”. Catch 22 was about absurd bureaucracy in World War II. We certainly have that in the “War On Terror”. The characters in M*A*S*H included principled surgeons and nurses at odds with pragmatists and corrupt officers. I knew both types, and every day we were in “The Office”, where loyalty, accomplishment, humor and friendship are often disrupted by disloyalty and politics.

An unfortunate event took me back to Site Three despite the Major’s claims. The day after I got back from R&R in Greece a lightning storm passed over Baghdad. By then the third site, Site Four on FOB Justice, the one that I was originally supposed to lead, was operating. Lightning was within striking distance of all three sites and the balloon at Site Three was hit. The crew did a fantastic job to recover it and get it on the tower but it was daylight so while they were trying to patch the holes and find all the other damage an RPG was fired through it, missing one of the crew by a few feet.

Being without a PTDS system in that part of the city, after getting used to the coverage it provided, was something the Army couldn’t stand. General Petreus himself had noted the system’s value but since another balloon wasn’t available the one at Site One was deflated and sent to Site Three. I was sent back to oversee the preparations for inflating the balloon and getting that site back in operation.

They sent me back to Site One, a gloomy place, where I stayed until my second R&R at the end of January. Judi and I met in Paris for that and then in February of 2008 I worked at Site 4 on FOB Justice, which is where they hung Saddam Hussein.

There were only two other Lockheed employees at Site One, where I would spend all but a few weeks of the next seven months. Lockheed wanted all sites to have twelve men assigned to them but ten was much more common. For a while there were eight as Site 3. I was the twelfth man at the time at Site One. My position there tenuous and my future insecure. I don’t know what the rumors were but none of them benefited my reputation. Another thing that made my stay at Site One a risk to my employment was the pack mentality. The men at Site One were a pack, with alpha and subordinate members and submissive members too. I was none of those. My position in the pack was more like a wounded outsider and some of the others smelled blood.

I felt it from the first night (I was put on the night shift) and dealt with it effectively. For example when I was accused of having pornography on my computer, a violation of General Order Number One, I invited them to seize my computer but I didn’t admit or deny anything and then I filed an identical complaint against my accusers. That made the affair more complicated and the accusations were withdrawn. It was easy to thwart them. The one who filed the “complaint” left the site and took a flight home without telling anyone. He just disappeared one day and no one knew what happened to him until weeks later when he was home in Texas.

Many who work in war zones, and elsewhere, operate according to non-integrated philosophic systems based on doubts, wishes, faith, fears, and slogans rather than reason. The predictable outcome being disarray to greater or lesser degrees, to which any of their many ex-wives, step, custodial, or non-custodial children could attest.

Eventually I prevailed by simply doing my job well and taking on tasks others neglected. The UTAMS tech that picked us up at the airport the first day had been gone for months so that system had ceased to function. I volunteered to fix it which meant road trips to every corner of the VBC and working on top of eight guard towers. Some of the crew respected that sort of thing and everyone eventually left me alone.

Ed Rusk was one whose respect I was glad to receive. He was a Marine Corps drill instructor, usually good to be around and the most foul mouthed man I’d ever known. Every sentence Ed uttered included expletives, often loudly inserted, that he’d rain on you if you made a mistake that created a problem for him or anyone else. He was funny about it without trying and he would, much less readily, recognize the good qualities in those he worked with. On those less frequent, but not rare occasions, when he’d point out a job well done the guy he was talking about was always glad. I was.

I also coped with ostracism and other stresses by turning to Judi. Thinking of her, writing to her and conducting video chats with her became a huge source of strength and a daily escape.

In May, after a full year out of the United States I went home for three weeks. Delaware is a great place to live and I love my home there. Tax laws affect behavior and there’s no better example of that than how the break that I got on my federal income tax kept me away. The law says that if you are out of the United States for 330 days out of any consecutive 365-day period you are exempt on the first $84,500 of income. That’s a lot of dough so I stayed off U.S. soil for 11 months. It was the longest period I’d ever been away from home and returning to the house I built to be with the woman I love was beautiful. Three weeks went by in a flash.

In March of 2008 I asked to be transferred to Afghanistan. The request was granted so my destination on May 27th was Waza Khwa, Paktika Province, Afghanistan by way Kuwait and Bagram Air Force Base, south of the city of the same name founded by Alexander the Great.

Waza Khwa

June and July, 2008 – Fire Base Waza Khwa, Paktika Province

Balloon Wars Part 4 (chapters 82 through 94)

The C-17 from Kuwait landed at 3 AM and the next flight the flight to Waza Khwa wasn’t until late in the mourning so I waited at the USO and tried to sleep, but I couldn’t. After sunrise I saw the Hindu Kush mountains for the first time. Bagram is on a 5000 foot high plateau. The air is cool, dry and clear so the mountains seem nearer than they are. I compared the view and the feeling with what I’d seen and how it felt in Iraq when I first got there. My first hours in Afghanistan were much better.

The mooring platform and some of the crew had been on Site W in Waza Khwa for six months but they hadn’t started operating the system. Lockheed’s country manager said they were nearly ready to inflate the balloon and if I got there in time I could help so I didn’t stop to rest in Bagram even though by the time I landed there I’d been traveling for 26 hours.

All the flights in Baghdad were in Blackhawks. The trip to Waza Khwa was my first flight in a Chinook and there would be many more. We stopped five times on the way for people to get out and to drop off supplies and mail and to load stuff in too. I helped at each stop. Eventually I was the last passenger and the only gear left was mine. By then it was early afternoon and I’d been traveling for thirty-six hours. The terrain hadn’t changed for the last hour so there was no point in any more sight-seeing. I had to lie down so I stretched out on the seats which were webbing riveted to aluminum tubing. They’re uncomfortable for sitting but lying on them is worse.

It occurred to me that I didn’t have to get off the flight when we got there. I’d seen nothing but dessert, dry riverbeds and low, utterly barren mountains for many miles and each outpost was worse than the last. At each I dreaded someone in the flight crew would mouth the words, “Waza Khwa”, or “This is you” and I would have to get out to stay at one of these extremely unappealing places.

When we finally got there we passed the FOB and turned back to land into the wind. What I saw produced the same dread I’d felt at the other stops. I didn’t want to be here either and I wished again that it wasn’t the end of the flight. But as we flew over the perimeter wall, on the south side of the helicopter landing zone I saw the balloon site.

By then the thoughts of what I’d done and where I was had become dark. When I saw the mooring platform and the site from the air my mood darkened more. Things weren’t right. The manager in Bagram told me that they were ready to inflate the balloon, which was why I pushed so hard to get there, but they weren’t ready. The tower wasn’t up, the mooring cone wasn’t attached to it and there was no one on the platform working even though it was the middle of the day. The site wasn’t even finished. Piles of stone were on the ground still to be spread and what was really disturbing was that there was no blast protection around three sides of the GCS, the Ground Control Station or the TMOS (Transport and Maintenance Office Shelter) and neither had overhead protection, no detonation screen or even sand bags. The two shelters we would occupy twenty-four hours a day were exposed, and the site was in one corner of the FOB on the perimeter wall which was just one Hesco® tall, or about six feet. If the site had been graded for Force Protection it would have gotten an “F”. I thought again that I could just stay on board and go back to Bagram and then home. I even hesitated when they told me to get off but I was too tired to go back so I put on my backpack, picked up my two duffels and walked down the ramp.

I’d remain in Waza Khwa, Paktika Province, with an unusual assortment of co-workers, for almost two months. Some of the men there were the bottom of the barrel. Within a few minutes of getting there the site lead, who had worked for Telford at Site One in 2004, told me, “This isn’t Iraq. We don’t work at that pace here”, and he repeated it until he realized I wasn’t going to slow down. Not that I was particularly driven, but I did make the others see just how far they’d slid.

What happened was, Site W was supposed to be Site T but when they tried to ship the mooring platform to FOB T (the current DOD security review redacted the name of the FOB) they discovered the truck couldn’t negotiate the mountain switchbacks so they looked around for another site. Waza Khwa was selected but it took six months to get everything together at the site. It didn’t have to take that long but it did and the crew, or a portion of the crew, waited, doing little more than keeping air in the tires. The fact that those guys were in the middle of nowhere doing nothing became a program wide joke.

There was one crew-member during that early period at Site W I like. He got there shortly after I did. He didn’t know anything about balloons but he knew all about the computer operating systems, including Unix, and he was curious. Like me, he wanted to know everything he could about the system. And he was teaching himself the Welch language. The majority of the guys at the sites played video games or watched TV between times “in the box”. This guy read manuals and listened to his language tapes.

The first two weeks would be spent preparing to inflate the balloon. That went reasonably well. It only took a couple days to get it fully operational. But then we did nothing with it for another two weeks because the Polish Army unit that was there either didn’t know what to do with it or had no use for it. They were a civil affairs unit so they were glad to avoid the Taliban, who didn’t seem to be around much anyway.

Eventually the Poles gave us daily assignments but they were nothing but route scans. For most of July we’d spend all day and night watching the dirt roads between villages that had almost no traffic on them. I was on the night shift and there were many nights when there was literally no one within sight. There were no missions to watch. The Poles rarely left the FOB and the Americans who were there, members of the famed 101st Airborne Division, ventured outside even less.

The society was so far behind that at night, for as far as I could see, and under the best conditions I could see sixty miles, no more than ten lights were shining. A couple villages had some streetlights powered by solar panels but otherwise the countryside and villages were utterly dark. The village of Waza Khwa had two cobblestone streets whose length were about a quarter mile each and those were the only paved streets or surfaces we could see. The entire province, which has a population of 400,000 people has 150 miles of paved road and it’s three times bigger than Delaware, which has 14,000 miles of surfaced streets and highways.

The Karez

Balloon Wars Chapter 87

There is one form of infrastructure I found fascinating. It’s a feature on the landscape I discovered the first time I operated the camera at Waza Khwa; a public works project that proves the Afghans are among the toughest people in the world with one of the best work ethics. It’s the way they get water from where it is to where it wasn’t through what Persians call a Qanat, which in Pashto is called a Karez. What I saw from above were crater like depressions in the ground placed about twenty meters apart that went from the south side of Waza Khwa to the neighboring village, Wasel Kheyl. On studying the 5 meter CIB (Controlled Image Base) aerial photos that were part of the background imagery in the CLAW (Control of LYNX and Applications Workstation) display I found these strings of bomb crater like holes to exist just about everywhere. The string outside the FOB was several hundred meters long but elsewhere they were several kilometers. No one at the site knew what they were so I looked them up on the internet. Since I didn’t know what I was looking for it was a more difficult search than most but eventually I found the answer and was amazed. The fact that none of us had ever heard of this ancient means of conveying water was pretty interesting too.

The builders pick a spot where there is or likely to be underground water, often at the base of a mountain, and dig a well there. They then dig holes on a line from that well, the “Mother Well”, to where they want the water for use on the surface. Several factors affect how far apart the intermediate holes are spaced but they can be much further apart than the ones I could see around Waza Khwa. Then they dig tunnels from the bottom of one hole to the bottom of the next allowing the water to flow between them until it eventually reaches an outlet at a garden, field or reservoir.

Excavating the tunnels between the holes is the nearly unbelievable part. It’s all handwork of course, in almost any kind of ground and at depths of tens and even hundreds of meters! In Iran, where the Qanat was invented, the deepest channels are over two hundred meters underground. It can take decades for a skilled team, typically four men to finish a Karez, which will be of benefit to the builder’s descendants and their communities for centuries. Ownership and use of the water is according to custom and Shari’a law. The Kitab-i Qani, the Book Of Qanats, written in the ninth century, is one such code.

It’s an amazing feat that requires specialized knowledge, skill and courage. Once I learned what they were, every time I saw one from the balloon camera or from the window of a helicopter I admired the Afghans who built them. The fact that I had no knowledge of their existence illustrated how little I understood about the people and their history. Qanats are an outstanding, perhaps the quintessential, example of what Middle Eastern man can produce. They require cooperation and long term commitment as conveyed in the instructions by the emissary prophets Moses, Jesus and Mohammed and they’re significant in an anthropological sense. Survival depended on controlling the environment by digging canals and Qanats in Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. Despite all this I had no idea what they were. My Western education and none of my reading had informed me of them. I’m not a highly educated person and I haven’t read everything but I know more than most and I know the men with me in Iraq and Afghanistan had less knowledge than me of Qanats, prophetic teachings and anthropology. It’s little wonder we haven’t won the hearts or minds of the people in Waza Khwa or that they don’t make their hearts available to us.

Captain Ellis

Balloon Wars Chapter 86

Our medical officer on FOB Waza Khwa, Captain Ellis had been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan six times. He was bitter about that but he was a good officer and did his job well. One day while he and I happened to be shaving at the sinks in the shower house at the same time a Specialist came in and told him the people he was supposed to meet at 1400 were at the ECP. He looked at his watch and he said, “Let ‘em wait. They can ‘insha’Allah’”. He said the mandatory Islamic response for anything that one plans to do, which means “if God wills” as if to say, “They can kiss my ass.”

I asked him what was his meeting about so he explained how pharmacists poison their customers in Afghanistan. They sell medication to the parents of sick children by the color of the pill. Red pills cost more than another color, say blue, which are more than another, maybe yellow. No matter the illness or symptoms the patient gets what he pays for, by color.

Ellis said, “I had a three year old brought to me, and a four year old, another kid was 11. A thirteen year old was brought in three times. Every time I had to give him CPR. The last time he died. He was on twenty different meds. His parents kept buying more expensive colors, ‘till he died. I can’t stand this any more. I hate the damn army. These guys that are waiting outside, the pharmacists, I asked them to come in here to talk about how they’re killing people and they blew me off. So I had ‘em arrested. They’re sittin’ out there now in zip cuffs. I’ll teach them to mess with me.”

He continued. “There’s a doctor in one of the villages too. He’s not very good but he is trying. These pharmacists are another thing. Nothing matters to them but the money.”

He was a good medic, not a doctor, but the people from the nearby villages came to the FOB for help with conditions that were way beyond what Ellis was officially qualified to handle. His boss, a Colonel in Bagram, ordered all the medics on the FOBs not to treat any of the locals. Captain Ellis did it anyway.

Before I left for the last time I saw a man with a six year old boy in his arms on the FOB. Blinding eye diseases are endemic in Afghanistan and eye infections in children are common. The boy eyes were severely infection. If the father had acted sooner it wouldn’t have been necessary but Ellis told him to bring his son back the next day so he could perform surgery to remove his sons eyes. Being forced to deal with such matters was why Ellis said he hated the Army.

The Good and The Bad

August, Sept and October, 2008 – Zormat, Bagram, Ghazni and Iberia

Balloon Wars Part 5 (chapters 95 through 104)

The plateau we were on was 7500 feet above sea level, half a mile higher than Denver. That coupled with clean air and no light pollution made the view of the stars at night magnificent. It would become miserable in the winter but in the summer the weather was good and it made me glad I wasn’t in Baghdad.Weather is a constant concern for balloon operators with the main meteorological hazard in Waza Khwa in the summer being dust devils that would build on the desert most afternoons. On July 25th one hit the balloon breaking the tether. The guys on duty sent the command to open the helium valve and deflate the balloon. The Army found it a few miles away and drug it back. They literally drug it with a truck. Without a balloon we were shut down so a few of us were sent to other sites. I went to Site Z, which was on FOB Zormat about a hundred miles northeast but the balloon there was damaged by Taliban rockets the day after I got there so I only stayed for eight days. One of the rockets landed about thirty feet from me but I was behind cover. If I hadn’t have been it would have killed me. Conditions there were unsafe and the crew was incompetent and hostile so I was real glad to leave.

Traveling in the war zones can be difficult and time consuming. There are no published schedules and delays are common. It took six days for a flight to come into Zormat and when it did I took it. It almost didn’t matter where it was going because anywhere was better than where I was. It turned out that the Blackhawks that stopped in Zormat were taking a General and some of his staff to Salerno, a big FOB in Khost Province that had a runway so from there it took less than a day to land a ride on a C130 to Bagram. I waited with soldiers from FOB Tillman who were on their way home. Listening to their stories and their genuine interest in mine really lifted my spirits.

I was stuck in Bagram until the end of August waiting for the new balloon and equipment to come for the site in Waza Khwa. While there I worked on the inflation procedure and exercised with Navy Seals, Air Force Special Forces, Recon Marines and Army Rangers. SF units from France and Canada were at the big gym on the west side of the base too and it was fun to watch all the warfighters work out their frustrations after a hard days work. It was a little disturbing too which caused me to research what the lasting effect of their experiences might be. The book “On Killing: The Pyschological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society” by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman was enlightening.

At the end of September I was due for R&R which I took with my lovely wife in Spain and Portugal. By then I was a full-fledged expatriate. Being out of the United States so long made me less aware of American politics, professional sports and other things that I was very interested in before. There were good and bad aspects of that status, but it was undeniable that the behavior modification that the tax policy produced had its affect. I didn’t mind discovering what things didn’t matter.

When I got back to Baghdad after my first R&R they told me that I wouldn’t be in charge at Site Three. Losing that job was a disappointment and a surprise and they hit me with a significant change to my status when I got back to Bagram too. This time it was good news. I was to join two others on the “Tiger Team”, who are the people who tend to extraordinary events and needs and my first assignment was to plan the next site, which would be in the Afghan capital.

Wrap It Up

November and December, 2008 – Bagram, Kabul and Ghazni

Balloon Wars Part 6 (chapters 83 through 118)

From the time I got to Iraq until long after arriving in Afghanistan I hadn’t been “outside the wire”. Being on top of guard towers while working on the UTAMS sensors was very close and it gave a very good view of Baghdad but it wasn’t until October 20, 2008 that I was on the ground outside a FOB or camp in either country. That day I went to Kabul in a three vehicle convoy with the in-country PMRUS representative for the project and I was no longer a Fobbit. Despite his cynicism, and at times because of it the PMRUS rep was a good guy. Our meeting was at ISAF Headquarters in the middle of the city with a Navy Lt. Commander and an intelligence specialist who was a Department of Defense civilian employee. One of the SUVs blew a tire on the way back so our guards had to change it and form a perimeter to guard us while they did.

The second trip to Kabul was with a different PMRUS employee, a more senior manager. That trip kept us in Kabul for a few days and it included an excursion to FOB Julian, on the southern outskirts of the city.

That became one of my final duties. You have to have the right disposition and circumstances to work through long and repeated deployments in war zones. Due to loneliness, isolation, confinement, sleep deprivation and other stresses my disposition changed to the point where I wanted to go home so I wrapped it up.

I gave them plenty of notice and they even kept me on for another two months back home to write procedures but my time in the war zones had to end.

My time in Iraq and Afghanistan and in Port Canaveral, Florida and Akron, Ohio on the Persistent Threat Detection System had value. It was just worth the hardship. It’s interesting how that works out.

I wonder, as many others do, was the war in Iraq worth it? How about the one in Afghanistan? For thousands of American servicemen and their families and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and Afghans who were killed or whose happiness has been permanently lost the wars have been a terrible tragedy. If we were to meet them few of us could be callous or thoughtless enough to ask any of them if it was worth it.

It is true however that the Middle East, where Islam was born and violence committed in it’s name and for it’s sake, is different than it was before September 11, 2001. If the purpose of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was to focus the minds of the dictators on what could happen that has been accomplished. It’s possible the sight of Saddam Hussein at the end of a rope awakened Arabs in general to what could be and the rejuvenation that comes with Spring.

September 11 comes to mind too if the question is about what the meaning was to me personally. My son joined the Army after the World Trade Center attacks and I was in Iraq while he was there. My wife and I were aware of the events along the way as parents of a soldier and Judi was alone for almost two years as that parent and the spouse of a man “over there”. I got the news of Osama Bin Laden’s death from Dan. He called me that night and we stayed on the phone together as Judi and I watched. We talked about how world events of the previous nine years affected our family.

My time away was worth it. I was well paid and without knowing the ultimate value of the experience I wouldn’t have gone for much less. It wasn’t the first time I changed my life for the sake of the change and this time I came away with an expansion of one fundamental concept, home, and the truth about another, country. If before I left I had known I’d survive and what I would come to know I would have done it for nothing.

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM BACKGROUND

First journal entry minutes after an IED detonation.

Assessing The Surge is a NY Times web page with articles and videos that assess the effect of the "Surge" in thirteen Baghdad neighborhoods, including Jihad, the one closest to Site 1.

The Killing Fields of Baghdad

from March, 2008 is the second of Ghaith Abdul-Ahad's three film series. In it he visits Baghdad's killings fields on the edge of Sadr City. The scene of thousands of sectarian murders over the previous three years, it is a desolate and evil place: "Only the killers and the killed ever come here" says Abdul-Ahad. Here in the thousands of graves marked with only scrap metal and junk lie the victims of the Shia militia gangs.

Baghdad's rich tradition in tatters was written in 1998 by Anthony Shadid, the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist who died while covering the uprising in Syria in 2012.

"Surreal Mother & Child" was an original oil painting for sale at the bazarre outside the big PX by an Iraqi artist whose name I didn't record.

June 10, 2007 Journal Entry about social contact with Iraqis.

Charles Lindholm is a professor of anthropology at Boston University and his book, The Islamic Middle East: An Historical Anthropology is an anthropologist's perspective on the history of the Middle East that places Islam in context with the other conditions that have shaped the cultures of the tribes and ethnicities of the region.

Koranic Mythology Behind Al-Sadr's Mahdi Army NPR's Mike Shuster reports on the mythology behind the Mahdi army, the militia supporting Iraqi insurgent leader Moqtada al-Sadr. The group has invoked the mahdi, an important Koranic symbol, to lend religious significance to their fight. (aired August 24, 2004)

Asia Times Online article on the motivation behind Muqtada al-Sadr's call for a cease fire in the summer of 2007.

Blast radii of munitions used against Iraqi and coalition forces.

© Robert A. Crimmins

Getting Used To the Racket, Rockets Stars and Stripes article in the September 6, 2007 edition about the frequent indirect fire attacks on FOB Loyalty.

June 15, 2007 Journal Entry about driving across the VBC at night.

Mahdi Army uses "flying IEDs" in Baghdad is a LongWarJournal.org article about the use of Improvised Rocket Assisted Munitions, IRAMs, against FOB Loyalty on April 28, 2008 and elsewhere.

Old prison a chilling reminder for Iraqis was in Stars and Stripes on April 3, 2005. It's about the Iraqi secret police headquarters and prison that became FOB Loyalty.

Six Questions For Wesley Morgan is a short interview with a college sophomore who spent the summer of 2007 in Iraq at the suggestion of General Patraeus.